Every medical device contains pieces of the Earth. They shouldn’t go to waste.

Like most products, medical devices don’t originate at the point of use. To get to patients and providers who need them, they require a complex web of trade and inputs—including rare metals and costly components, often pulled from all over the world.

These resources make modern healthcare possible—but also vulnerable.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, critical supply shortages forced health systems to delay or forego treatments. Ongoing trade and geopolitical disputes compound the threat, with major medtech and clinical organizations urging lawmakers to protect device stocks.

Hospitals can help maximize the service life of their “single-use” devices (SUDs) through reprocessing programs. Every reprocessed SUD represents a critical resource that was protected—and a patient that could go untreated if that resource was lost. In 2024 alone, hospitals bought over 36 million reprocessed SUDs worldwide from AMDR member companies.

Reprocessing is a necessary component of smart supply chain strategies.

Let’s look inside one commonly-reprocessed SUD—a pulse oximeter sensor—to understand why.

The World Inside a Pulse Oximeter Sensor

Pulse oximeters shine light through a patient’s body to measure their blood oxygen level. They are essential in emergency medicine and the diagnosis and treatment of numerous ailments. While “all-in-one” pulse oximeters can be used at home, the image depicts the type of pulse oximeter sensor used in hospitals and reprocessed by some AMDR members.

Pulse oximeters shine light through a patient’s body to measure their blood oxygen level. They are essential in emergency medicine and the diagnosis and treatment of numerous ailments. While “all-in-one” pulse oximeters can be used at home, the image depicts the type of pulse oximeter sensor used in hospitals and reprocessed by some AMDR members.

These little sensors may look simple—but inside of them are rare resources and components from many different countries, including those most vulnerable to supply disruptions.

Below are five examples that show how everyday healthcare depends on the stability of global extraction, manufacture, and trade networks (click on the resource to learn more).

![]()

In the pulse oximeter sensor: Semiconductor materials are essential for modern electrical chips and circuitry, including those which enable the device to function. The image shows a large chip for demonstration, but semiconductor materials can be used in extremely small components, and virtually all modern electronics require them in some amount.

![]()

Common semiconductor materials include silicon, of which nearly 80% is produced in China. Chip manufacturing is complex and time-consuming, and is concentrated in East Asia, especially Taiwan, China, and South Korea—though production is increasing in the United States.

Given their strategic importance and geopolitical tensions between major producers, global trade in semiconductors faces intense scrutiny, tariffs, and long-term vulnerabilities.

In the pulse oximeter sensor: Copper forms the wiring and spring contacts that move electrical signals between the sensor and display.

Most refined copper comes from Chile and Peru, which together supply nearly one-third of global output.

Strikes, droughts, power outages, and mine collapses can disrupt extraction and slow shipments, raising costs across manufacturing.

In the pulse oximeter sensor: Trace amounts of gold are often used as plating on cables and connector pins to protect them from corrosion. Other metals used for this purpose can include silver, nickel, and tin—but gold is a particularly common and valuable option.

A globally traded metal, gold is primarily mined in China, Australia, Russia, Canada, and the United States.

Gold prices rise sharply during supply shocks or global uncertainty, which pushes up component costs even for tiny amounts.

In the pulse oximeter sensor: Palladium is commonly used in tiny ceramic capacitors that help stabilize electrical signals. Alternatives can include nickel, silver, or tantalum, though none of these are immune from price volatility or supply chain disruptions.

More than 75% of the world’s palladium comes from Russia and South Africa.

Geopolitical tensions, potential sanctions, or mine interruptions in these countries can cause global price spikes that ripple through electronics manufacturing.

In the pulse oximeter sensor: This trace metal enables the red and infrared LEDs that measure oxygen saturation.

Nearly the entire global supply of gallium is refined in China.

In August 2023, China imposed strong export restrictions on Gallium and other critical metals. For several months, exports of these metals dropped to zero, creating global shortages for LED and chip manufacturers.

Preserving Care Means Conserving Critical Resources

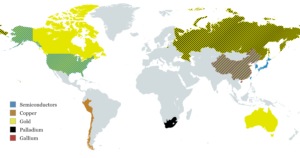

With all of these resources taken together, including only the main producers, the “world inside a pulse oximeter sensor” looks like this:

That covers roughly 40% of the Earth’s landmass and 30% of the global population.

For pulse oximeter sensors to exist, this mosaic of nations must maintain a minimum of cooperation and trade. Furthermore, the concentration of these resources in so few countries means even domestic turbulence in one can ripple through the entire global supply chain.

And the pulse oximeter sensor is just one example—every medical device depends on such vast, fragile supply chains. When we discard a device prematurely, we waste not only the product but the energy, labor, and precious materials that built it.

In AMDR’s policy agenda, we urge governments around the world to adopt regulatory and procurement frameworks that prioritize the use of reprocessed SUDs.

That is because, in addition to considerably reducing costs and greenhouse gas emissions, reprocessing conserves these critical resources. It keeps them in circulation for longer, protects patient access to essential care during crises, and reduces our dependence on materials that cross oceans before they ever reach a patient.